On Reading Sebald

A journey through memory, place, and text

Reading Sebald is a personal experience. Sebald does everything he can to convince you that everything in the book really happened, and that the main character actually existed. He stitches his narrative into real, historically massive tragedies, borrows biographies of famous people, and uses his main device: he adds photographs, creating a documentary effect.

Disclaimer: I’m not going to retell Sebald’s plots. There are tons of articles about that in your favorite publications. Please read this first of all as an experience of reading.

I bought my first Sebald book in Hong Kong. It was Vertigo. After a week of moving between Hong Kong Island and Kowloon — sometimes by ferry, sometimes by metro — I finished it pretty fast.

The next novel I picked up was Austerlitz. Over the last few years I kept seeing it in bookstores all over the world — San Francisco, Boston, Madrid, Paris. Austerlitz always stood out on a bookshelf. The title and the photograph of a boy dressed as a page on the cover blurred the border between fiction and nonfiction. Tolstoy readers could guess that it’s fiction about 1805, while the photo evoked an undeniable sense of real historical events.

Vertigo is a perfect place to begin with Sebald: you can taste his main techniques, watch how facts are woven into a narrative, and feel how the photograph creates an extra layer of storytelling. After that you can move to Austerlitz, which — no more, no less — can change the world around you forever.

Like the main character of Austerlitz, Jacques Austerlitz — who begins to hear echoes of his past in the resonances throughout the world — you too, traveling with this book in your hands, start rhyming yourself, your space with the book and, at the same time, with reality. You crack open pages you would never have touched in your life.

After Hong Kong, for the first time in three years since leaving, I found myself in Prague. I lived in this city for many years, and it still speaks to me in a language only we share. Austerlitz was with me. And by some strange coincidence, exactly when I arrived, the novel’s story also unfolded in Prague and reached its point of no return.

At that point the hero hears, for the first time, a word unknown to him until then — Veverka — in a language that seems foreign to him. It opens a huge lost world. So I too hear vavyorka in my dead language, and the world takes on new colours. The harmony of Czech and Belarusian languages is the first moment that begins to braid my own reality with Austerlitz’s world. A unique position — like there’s a rhyme that doesn’t exist for anyone else.

The streets and parks of Prague begin to reverberate with the protagonist through Czech words and events that are woven at the same time into grief and into the place where you were born or lived the best years of your life.

Time and memory are central in Sebald’s work. You can hear echoes of Proust, Arendt, Mann, Grass. If Merab Mamardashvili said that memory is the worst thing that could happen to a human being, Sebald does the opposite: he tries to find the best place for himself between living inside memory and floating in a river with no beginning and no end.

….since they were not fenced off, it was possible, if you had the nerve, to go right up to the very edge of these enormous pits and look down into a depth that went thousands of meters below. A more terrifying sight, Jacobson writes, is hard to imagine: you stand on solid ground and see, only one step away from you, the gaping void, and you understand that there is no crossing here, only a thin rim — on one side ordinary life, taken as something self-evident, and on the other its absolute, incomprehensible opposite. — W. G. Sebald, Austerlitz

Sebald is like the sky in Hong Kong. You see the pale and delicate reflection of the pink sunset on the tops of those skyscrapers, you try to slip through the streets to catch at least one place where the sky touches the ground, but you never make it in time. It dissolves into night, and the next day you start again.

Moving with the novel from Prague to Paris, I met the last events of the book for myself exactly there. The Luxembourg Garden, where the hero walks with his new acquaintance and tries to grab at any thread leading to his father, once became an important point for me too. My favourite Paris route always began at Canal Saint-Martin and ended in the Luxembourg Garden.

After multiple trips, I was coming home from London to Amsterdam. London was also one of the main places for the novel, and if I changed Amsterdam for Antwerp, I would repeat exactly the same route that happened to the main character.

I’m purposely skipping the part about the plot and main story of the novel. I intentionally tear events into pieces because I want to save the experience of opening this terrifying box for those who have not yet read Sebald’s novels.

But one moment matters for understanding. In his endless search for his parents, Austerlitz finds film footage from a concentration camp in what is now Czech Republic, where his mother most likely died. To absorb every millisecond and catch any trace, he slows the footage down several times. And in that slowed time a kind of demonic abyss of unconscious detail begins to appear. Sebald knows exactly what he’s doing. And you no longer understand how many layers you’ve fallen through — but the dread keeps growing. In one flicker of a frame, Austerlitz thinks he can make out his mother, as if she never existed at all. Walter Benjamin describes this shift with particular precision:

As a result it becomes obvious that the nature revealed to the camera is different from the one revealed to the eye. Different above all because the place of space shaped by human consciousness is taken by unconsciously mastered space. And if it is normal that in our consciousness, even in rough outline, we have an idea of a human gait, then consciousness knows nothing about the pose a person takes in a fraction of a second of a step. We may be familiar with the motion of taking a lighter or a spoon, but we hardly know what happens between the hand and the metal — not to mention how the action changes with our state. This is where the camera enters with its auxiliary means: drops and lifts, the ability to interrupt and isolate, to stretch and compress an action, to enlarge and reduce an image. It opened for us the realm of the visually unconscious, just as psychoanalysis opened the realm of the instinctively unconscious. — Walter Benjamin, The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction

Sebald plunges you into his abysses — and helps us find broken connections: with home, with the place where you were born, with relatives, even with parents. He slows us down, more and more, like a film in slow motion, where you finally start seeing the most terrifying frames. You meet your main fear. But this movement has one healing property — it moves you toward your own life. It’s easy to enter someone else’s life. Entering your own is scary — but incredibly rewarding.

Afterword

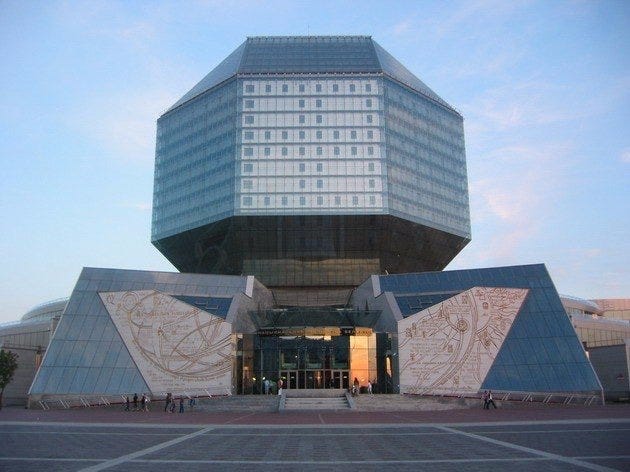

Architecture was an important companion to the whole novel. Austerlitz studies architecture and its invisible patterns. I don’t know if Sebald read Christopher Alexander — more likely no than yes — but I don’t understand how they didn’t collide.

Buildings speak to us in their own language. When a brutalist Paris library turns into a structure designed to repel readers, and at the same time into a way to prove something to someone, the reader is expelled forever from the halls of that library.

People build the most perfect buildings, and right when they reach perfection, a new weapon appears — and turns these perfect towers and moats to ash.

—

While writing this essay, I searched my archive for photographs that could accompany the text. For the keyword Austerlitz, I found a frame from an exhibition by the graphic designer Karel Martens at the Stedelijk Museum. It included an essay about Austerlitz and an invisible reference to Christopher Alexander. And I was genuinely stunned, because at that point, his book had accidentally landed in my hands — The Timeless Way of Building — and I was already halfway through.

As Celine Nguyen writes in her essay “writing is an inherently dignified human activity“:

Human behaviour is imitative. We read because the people we admire do so. We begin to admire the writers that have altered our ways of thinking. And often, we seek to imitate our new idols—by beginning to write ourselves.